Africa's Antibody Gap: Bridging the Divide in Biologic Access

The pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries are rapidly evolving, driven by significant scientific advancements. One of the most impactful innovations in medical science is biologics—medications made from living organisms or their products, such as proteins, cells, and tissues. Since the discovery of the first biologic drug, insulin, used to treat Type 1 diabetes over a hundred years ago in the 1920s, biologics have come a long way, expanding to treat a wide range of conditions, including cancer and autoimmune disorders.

Biologics have become a significant part of the treatment paradigm in the US, where the FDA approves one of the highest numbers of new drugs globally. In 2023, nearly 40% of all FDA approvals were for biologics. Over the past three decades, the proportion of biologics among new FDA-approved drugs has practically tripled, from 14% between 1996 and 2000 to 26% in 2016, and reaching current levels. Combining insights from Europe, we find that nearly 50% of cancer drug approvals were for biologics in the first quarter of 2024.

On a more global scale, there has also been growth in the inclusion of biologics in essential medicines lists (EML) for international health agencies. One of the most globally recognised EMLs is the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (WHO EML), a guide created by the WHO to help countries decide which medicines should be available to their populations. It is a priority list of the most important medications for treating prevalent diseases and health conditions. Today, the WHO EML has over 125 biologics (including vaccines, blood coagulation factors, immunomodulators, and many others).

As more biologics come to market, a unique class of biologics has become crucial in modern medicine - monoclonal antibodies (mAbs). mAbs are lab-made molecules designed to mimic the body’s natural antibodies and target specific proteins or cells involved in disease. What makes mAbs particularly powerful is their precision—by targeting specific molecules, they can treat diseases more effectively and with fewer side effects than traditional treatments. mAbs have revolutionised the treatment of a wide range of conditions, including cancer, autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis, and infectious diseases like COVID-19.

Regulatory and international health agencies have increasingly adopted this growing class of biologics, making mAbs highly accessible worldwide. By the end of 2023, the US FDA and the EU EMA had approved over 100 mAbs each. Additionally, the WHO EML includes over 18 monoclonal antibodies. However, these novel therapeutics come with a higher price tag than traditional small molecules. In the US, mAbs can cost anywhere between $10,000 to almost a $1 million per year at the list price level. Even in Europe, mAbs can cost between €5,000 to over €200,000 per year at the list level.

While the rise in the availability of innovative biologics is a testament to medical innovation in high-income countries, the story differs in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa. These high prices, in combination with health systems challenges and barriers to market entry of generic alternatives (known as biosimilars), have hindered broad access to biologics in Sub-Saharan Africa. A 2020 report showed that only 20% of global sales of monoclonal antibodies occurred in territories outside the USA, Europe, or Canada. However, Africa, accounting for 17% of the global population, represented only 1% of monoclonal antibody sales.

These challenges with access and availability of biologics in Africa mean that African patients are left with limited treatment options as drugs that significantly improve survival outcomes in severe diseases such as cancer, autoimmune disease, and diabetes struggle to be integrated into public health systems. This disparity may be one of the reasons why low-income countries saw only a 5% reduction in premature deaths from cancer between 2010 and 2015 compared to 20% in high-income countries.

Analysis Overview

This article marks the beginning of a multi-stage analysis assessing the availability of biologics in Sub-Saharan African countries, with a particular focus on monoclonal antibodies. The first stage centers on Nigeria, exploring access to biologics through three key lenses:

Regulatory Approval: When a drug is regulatory approved, it has been proven safe and effective, and a license has been granted to be sold and distributed in a country. This means it can be made available to buy privately at a price set by the manufacturer or distributor. This is a foundational step in making any drug available in a country.

Inclusion on the Ministry of Health Essential Medicines List: In the context of a fully functioning health system, drugs on the essential medicines list are intended to be available at all times in adequate amounts, in the appropriate dosage forms, with assured quality and adequate information, and at a price patients and the community can afford. Taking this lens allows an exploration of the prioritisation of biologics for public health.

National Health Insurance Reimbursement: National health insurance schemes reimburse some or all of a drug's cost, ensuring that it is financially accessible to the population. Decisions to reimburse are often driven by cost-effectiveness analyses, budget impact models, and unmet medical needs. Due to funding limitations and policy constraints, the accessibility bottleneck is most pronounced in this area, making it crucial to understanding access to biologics.

Monoclonal Antibody (mAb) Accessibility — Nigeria

Nigeria Assessment

The analysis in Nigeria revealed the following results:

In Nigeria, 6,078 drugs are approved by the National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control (NAFDAC), of which 107 are biologics. This figure includes branded biologics, biosimilars, and various formulations. When grouped by active ingredient, there are 68 unique biologics approved in the country. Among these, 13 are monoclonal antibodies.

While the 2020 7th Edition of Nigeria's EML lists 6 monoclonal antibodies, only 4 are NAFDAC-approved. Furthermore, when examining NHIS reimbursement—using the NHIS Medicines Price List as a proxy—only 4 monoclonal antibodies are reimbursed.

Monoclonal Antibody (mAb) Accessibility — Ghana

Ghana Assessment

The analysis in Ghana revealed the following results:

In Ghana, 7,120 drugs are approved by the Ghanaian Food and Drug Authority (FDA), of which 150 are biologics. This figure includes branded biologics, biosimilars, and various formulations. When grouped by active ingredient, there are 94 unique biologics approved in the country. Among these, 8 are monoclonal antibodies.

The 2017 7th Edition of Ghana’s MoH Ghana National Drugs Programme (GNDP) EML lists 8 monoclonal antibodies. When examining NHIS reimbursement—using the NHIS Medicines List as a proxy—only 1 monoclonal antibody is reimbursed.

Monoclonal Antibody (mAb) Accessibility — South Africa

South Africa Assessment

The analysis in South Africa revealed the following results:

In South Africa, 14,798 drugs are approved by the South African Health Products Regulatory Authority (SAHPRA), of which 304 are biologics. This figure includes branded biologics, biosimilars, and various formulations. When grouped by active ingredient, there are 107 unique biologics approved in the country. Among these, 45 are monoclonal antibodies.

While the November 2024 Tertiary and Quaternary Level Essential Medicines List lists 7 approved monoclonal antibodies, only 6 are SAHPRA-approved. Furthermore, when examining NHIS reimbursement—using the NHI Master Health Products List for tenders / contracts as a proxy—only 4 monoclonal antibodies are reimbursed.

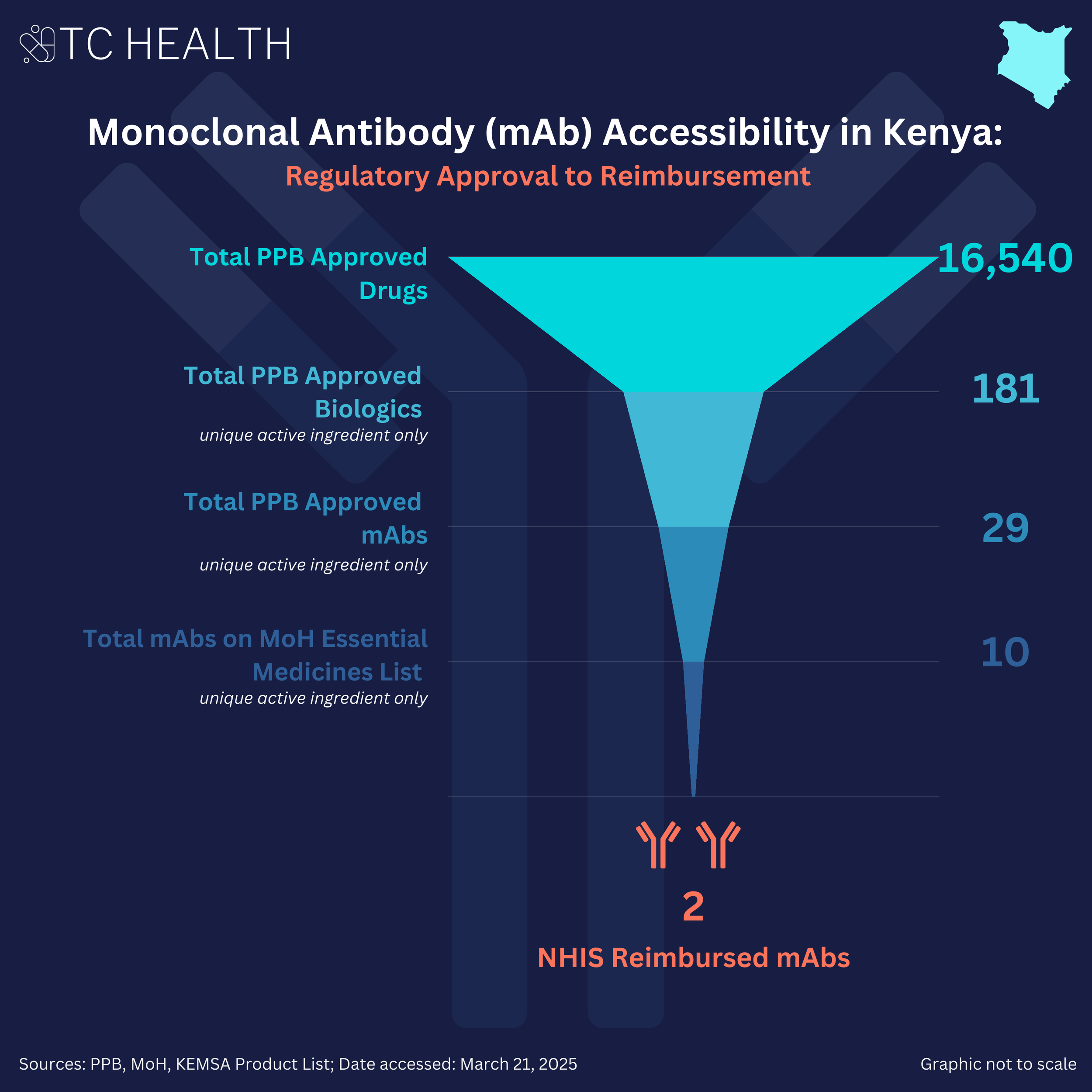

Monoclonal Antibody (mAb) Accessibility — Kenya

Kenya Assessment

The analysis in Kenya revealed the following results:

In Kenya, 16,540 drugs are approved by the Kenya Pharmacy and Poisons Board (PPB), of which 311 are biologics. This figure includes branded biologics, biosimilars, and various formulations. When grouped by active ingredient, there are 181 unique biologics approved in the country. Among these, 29 are monoclonal antibodies.

The 2023 Kenya Essential Medicines List published by the Ministry of Health lists 10 monoclonal antibodies. Furthermore, when examining NHIF / SHA reimbursement—using the Kenya Medical Supplies Authority (KEMSA) Product List as a proxy—only 2 monoclonal antibodies are reimbursed. The KEMSA Product List was used as a proxy as this agency is responsible for procuring and supplying medicines to public facilities, indicating that a medicine listed and priced on the list is likely to be available and reimbursed under public insurance like NHIF / SHA programs.

Monoclonal Antibody (mAb) Accessibility — Rwanda

Rwanda Assessment

The analysis in Rwanda revealed the following results:

In Rwanda, 2,286 drugs are approved by the Rwanda Food and Drug Authority (FDA), of which 52 are biologics. This figure includes branded biologics, biosimilars, and various formulations. Among these, 14 are monoclonal antibodies and, when grouped by active ingredient, there are 6 unique monoclonal antibodies.

The March 2024 8th Edition of the National List of Essential Medicines for Adults published by the Ministry of Health lists 4 monoclonal antibodies. Furthermore, when examining Mutuelle de Santé reimbursement—using the Rwanda Social Security Board (RSSB) reimbursable medicines list as a proxy—there are no monoclonal antibodies reimbursed. The RSSB reimbursable medicines list was used as a proxy as the Mutuelle de Santé community-based health insurance scheme has been administered under the RSSB agency since 2015 as part of efforts to harmonize Rwanda’s health insurance schemes.

Implications & Recommendations

The analysis reveals that while South Africa leads with 45 regulatory-approved monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), followed by Kenya (29), Nigeria (13), Rwanda (6), and Ghana (8), access remains a consistent bottleneck across all five countries. Despite varying levels of regulatory capacity, actual patient access remains low. Only 4 mAbs are reimbursed in both South Africa and Nigeria, 2 in Kenya, 1 in Ghana, and none in Rwanda, based on available reimbursement proxies. Rwanda’s case is particularly telling: though 4 mAbs are listed on its 2024 Essential Medicines List, none appear on the RSSB reimbursable medicines list, indicating that regulatory approval and even EML inclusion do not guarantee access. These findings suggest significant barriers to public access, likely leaving patients reliant on private sector procurement, private health insurance, or out-of-pocket payments (OOPs) for these high-cost therapies.

Notably, regulatory capacity appears stronger in Southern and East Africa, with South Africa’s SAHPRA and Kenya’s PPB approving more mAbs than their West African counterparts. This disparity may reflect differences in regulatory maturity, technical capacity, and historical experience with complex biologics, positioning countries with more robust regulatory frameworks to more readily engage with innovation. However, ongoing regional harmonization initiatives—such as the African Medicines Agency (AMA) and the East African Community’s Medicines Regulatory Harmonization (EAC-MRH) program—offer a pathway to strengthen regulatory alignment and capacity across the continent, potentially narrowing these gaps over time.

A notable limitation of this analysis is the dearth of up-to-date, publicly available information. Regulatory approval data, EMLs, and national medicines reimbursement lists often lag, with some countries' latest public records dating back to 2017. This gap complicates tracking which drugs are registered, included on essential medicines lists, or reimbursed under national health systems. Moreover, discrepancies between regulatory approvals and EML inclusion point to systemic inefficiencies in prioritising high-need biologics for public health.

Nonetheless, this analysis reveals the significant need to improve access to biologics in Sub-Saharan Africa. Cost-effectiveness remains a considerable barrier to biologics access in this region. Studies, including one by Gershon and colleagues, have shown that a one-year treatment course of originator trastuzumab, a widely used monoclonal antibody for breast cancer, is not cost-effective in any of the 11 Sub-Saharan African countries when assessed against WHO-recommended cost-effectiveness and GDP per capita thresholds. For trastuzumab to be cost-effective, the cost of treatment would require significant discounts (starting at 70% and up to 98% in some countries). Similar analyses for emerging therapies, such as GLP-1 receptor agonists for diabetes (i.e., oral semaglutide), indicate that substantial price reductions—up to 98%—are required to achieve cost-effectiveness. These cost-effectiveness challenges have resulted in significant implications for access to mAbs in the region. For example, although Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, considered including mAbs for the prevention of rabies in its 2018 Vaccine Investment Strategy, it subsequently decided not to fund these drugs on the basis of cost and cost-effectiveness considerations, meaning these mAbs would not be available to countries through Gavi’s vaccine support programmes.

Another factor influencing access is the disease burden profile in Sub-Saharan Africa, which differs from that in North American or European countries. Conditions like rheumatoid arthritis and autoimmune diseases, which drive significant monoclonal antibody use in the West, are less prevalent in Sub-Saharan Africa. This raises questions about the prioritisation of certain biologics in the region and highlights the need to align reimbursement decisions with local epidemiological needs. The mAbs that are reimbursed by the NHIS in Nigeria are primarily used to treat highly prevalent cancers in the country, such as breast and cervical cancer, certain prevalent autoimmune conditions, such as lupus, as well as conditions related to diabetes, which has a rising burden in the country.

Despite these challenges, several approaches exist that can improve the accessibility of biologics in the region. Regulatory approval and market entry of multiple biosimilars (generic versions of biologics) could significantly reduce the cost of biologics through intense price competition. For instance, in India in 2020, the cost of trastuzumab decreased by almost 80% compared to its original launch price in 2002 due to the availability of 11 competing biosimilars. Additionally, innovative payment models in Africa could help governments manage drug costs despite budget constraints by offering flexible, predictable payment structures like subscription-based, volume-based or outcome-based pricing, allowing for bulk purchasing and cost-sharing. These models make it easier for governments to plan budgets and ensure access to essential medications in resource-limited settings. Lastly, recent literature indicates that licensing agreements—where patent holders allow additional manufacturers to produce and sell generic or biosimilar versions of patented medicines in defined territories for specified uses— offer one potential pathway to improving access by enabling local production and reducing costs.

By identifying barriers and potential solutions, this work seeks to contribute to efforts to promote equitable access to life-saving therapies for African patients.

Key Takeaways from TC Health: As monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) reshape global treatment standards, access—not regulatory approval—has emerged as the most sweeping bottleneck across Sub-Saharan Africa. While regulatory harmonization efforts are gaining momentum, they must be matched by serious attention to reimbursement and financing. Without this, patients are left to navigate high-cost therapies through private insurance or out-of-pocket payments, leaving many vulnerable to catastrophic healthcare costs and undermining equitable access. As the rest of the world shifts away from traditional chemotherapy and steroids toward safer, more targeted biologics, Africa must prioritize access as the true gateway to progress.